A request came to me to provide an answer to the question of the Canaanite conquest, and how do we square that with the idea of a loving God (for background on this, go to Dan van Loon’s posts here and here). But having said that, I am now finishing the study I started earlier on this topic, so I will try to share a bit of my conclusions.

A. Is the war of conquest against the Canaanites Jihad? Genocide? Ethnic cleansing? We need to understand that what occurred in the books of Joshua and Judges was not Jihad. Let me explain.

According to the most Muslim traditionalists, the world is divided into two camps:

- The House of Islamic Peace (Dar al-Salam), where Muslim governments rule and Muslim law prevails.

- The House of War (Dar al-Harb), which refers to the rest of the inhabited world.

The presumption is that these two camps will compete and that fighting is inevitable. Therefore the duty of Jihad will continue, interrupted only by truces until all the world either adopts the Muslim faith or submits to Muslim rule. Those who fight in the Jihad qualify for rewards in both worlds — treasure in this one, paradise in the next. From the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad onward the word Jihad is used in a primarily military sense.

Commonly, Jihad requires Muslims to “struggle in the way of God” or “to struggle to improve one's self and/or society.” The four major categories of Jihad that are recognized are:

- Jihad against one's self (Jihad al-Nafs),

- Jihad of the tongue (Jihad al-lisan),

- Jihad of the hand (Jihad al-yad),

- Jihad of the sword (Jihad as-sayf).

Islam focuses on regulating the practice of Jihad. It is a call to all Muslims to engage in this struggle, ongoing and intentional. You will hear of fundamentalist Muslim groups who will declare a Jihad against a group or country (such as Al Qaeda against the US), but this is an extension of the central idea of Jihad.

Put simply, Jihad is a struggle that every devout Muslim is called upon to wage against the enemies of Allah. It is ongoing, and will not end until the conditions discussed above are realized. The best that the enemies of Islam can hope for are truces. The ultimate goal is submission of the world to Allah and the rule of Islam.

It is important to note that Jihad is mandated by Allah through the Qur’an, but it is declared by people (e.g., leaders), who also identify who the enemies are to be.

B. The focus in Scripture is on Yahweh war, or as it is incorrectly called, “holy war.” The term refers to war sanctioned by Yahweh (usually translated in our bibles with the phrase LORD, all capitals). But we need to note some important differences.

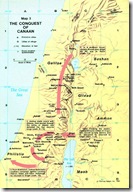

The conquest (and hence Yahweh war), was a single event, a unique event and limited event, lasting one generation, and was not meant to be a model of how future generations of Israelites should live and behave toward their contemporaries. It was an act of God, a call to take part in the Yahweh war. Yahweh war is not a feat of military prowess by the Israelites, or even their victory.

C. Genocide is a word sometimes used to describe the Conquest of Canaan. Genocide means the killing of an ethnic or culture group. In current usage, it is based on vicious self-interest, based on some view or myth of racial superiority, and is little more than ethnic cleansing.

The conquest of Canaan is never seen as ethnic cleansing, or as a mark of moral superiority. Nor is the action of Israel seen as a mark of oppression.

It seems, therefore, that we need to define our terminology. Jihad and genocide are not the same concepts as Yahweh war. To define the conquest of Canaan in these terms misses the point and clouds our understanding of the events. Our discussion can now move into the arenas of philosophy and theology.

When we do this, we find that there are no simple answers for this question. But a comment by N.T. Wright about the Conquest in his book Evil and the Justice of God (IVP, 2006) seems a good place to start:

“We look back from our historical vantage point – and post-Enlightenment thought has looked back from its supposed position of moral superiority – and we shake our heads over the whole sorry business of conquest and settlement. Ethnic cleansing, we call it; however much the Israelites had suffered in Egypt, we find it hard to believe that they were justified in doing what they did to the Canaanites, or that the God who was involved in this operation was the same God we know in Jesus Christ.

And yet ever since the garden, ever since God’s grief over Noah, ever since Babel and Abraham, the story has been about the messy way in which God has had to work to bring the world out of the mess. Somehow, in a way we are inclined to find offensive, God has to get his boots muddy and, it seems, to get his hands bloody, to put the world back to rights. If we declare, as many have done, that we would rather it not so, we face a counter-question: Which bit of dry, clean ground are we standing on that we should pronounce on the matter with such certainty? Dietrich Bonhoeffer declared that the primal sin of humanity consisted in putting the knowledge of good and evil before the knowledge of God. That is one of the further dark mysteries of Genesis 3: there must be some substantial continuity between what we mean by good and evil and what God means; otherwise we are in moral darkness indeed. But it serves as a warning to us not to pontificate with too much certainty about what God should and shouldn’t have done” (pp. 58-59).

Wright is saying that there must be a consistent understanding between what God understands as good and evil and our understanding of good and evil. If we judge the conquest of Canaan from our human, philosophical, ethical, moral standards in a way that is not based on God’s understanding of good and evil, we can very easily be presented with a moral and intellectual gap that may seem insurmountable.

In light of this, there are several questions we can address in the discussion in this issue:

- We have already discussed how the issue of Jihad in the context of Islam relates to the books of Joshua and Judges, whether it is the same thing as Jihad. How can we understand the idea of “holy war” in Joshua, can we see it as morally justifiable, yet condemn Jihad in the Islamic context?

- What of the philosophical-ethical issue of the conquest? Can we ponder it through our 21st century mindset, which leads us to interpret the conquest as ethnic cleansing or something similar?

- How can our understanding of the conquest square with the historical, grammatical situation of event, i.e., how did the Joshua and the people of Israel understand about the conquest?

- What are the theological issues attached to the question of the conquest? Can God’s command to destroy the Canaanites be seen as a viable command, something that had to be obeyed?

The discussion above is not an attempt to assuage the reality of the discussion, or pretend to offer a defense or apology for the conquest. It is merely an attempt to define our terms.

For my part, although the conquest doesn’t completely set with my view of the world, I do understand that we have to look at the event from the world perspective of ancient Canaan, and deal with the issue from that perspective, and not force our 21st century world view upon the event.

From there, I understand the event of the conquest in terms of God’s dealing with the Israelite people. This event wasn’t something out of context and out of character with God’s overall plan. As Wright says above, this is one of those times that God saw the need to get his boots dirty and his hands bloody in order to put the world to rights.

More to come.

0 comments:

Post a Comment